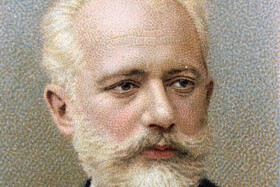

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il'yich

Tchaikovsky: a great Russian, a great Romantic - and a master of the lament

Who was Tchaikovsky?

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was perhaps Russia's most famous composer, as well as one of the very best Romantic composers alongside the likes of Beethoven, Schubert, Berlioz, Brahms, Chopin and Verdi.

When was Tchaikovsky born?

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born on 7 May 1840, exactly seven years after another great Romantic composer, Johannes Brahms. The two famously weren't big fans of each other's music. That said, Brahms managed to set himself against a fair few other composers. He also strongly disagreed with Franz Liszt, in a dispute that become known as the War of the Romantics.

Where did Tchaikovsky grow up?

Tchaikovsky was born in the small Russian town of Votkinsk. His family had a history of distinguished military service: his father, Ilya Petrovich Tchaikovsky, had served as a lieutenant colonel and engineer in the Department of Mines.

What was Tchaikovsky's most famous piece?

The Russian composer's most famous work is probably the1812 Overture from 1880. This short but rousing piece is a musical evocation of Russia's victory over Napoleon in the year 1812. Both the French national anthem (La Marseillaise) and the Imperial Anthem of the Russian Empire ('God Save the Tsar') are heard, but the piece memorably culminates in a majestic celebration of cannon fire.

There is much, much more to Tchaikovsky than one short (but admittedly very rousing) piece of music, however. Among other things, he also composed six wonderful symphonies, a famous Violin Concerto, and two Piano Concertos. Indeed, Tchaikovsky's first Piano Concerto is one of the most famous and best loved piano concertos ever composed.

Three more famous pieces by Tchaikovsky are the music to the ballets Swan Lake, The Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty. Swan Lake, in fact, is now the world's most frequently performed ballet.

What are the most famous pieces from Swan Lake?

Swan Lake's most famous moments include Act I's elegant Waltz, the exuberant Dance of the Cygnets, and the Black Swan pas de deux.

What are the most famous pieces from The Nutcracker?

The most famous moments from The Nutcracker include the March of the Toy Soldiers, the Pas de Deux, and the beautiful, almost otherworldly Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy.

Who did Tchaikovsky marry?

Tchaikovsky had a successful life, in musical terms, but not an especially happy one. Indeed, his life was marked by frequent crises and outbreaks of depression. He had more than his fair share of troubles to contend with. For example, he was separated from his beloved mother at the age of ten, and sent to a boarding school hundreds of miles away.

Later on, Tchaikovsky had to deal with the death of his close friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein. Then came a failed marriage. Tchaikovsky married Antonina Miliukova, but the marriage was not a success.

One theory suggests that Tchaikovsky proposed marriage to Antonina in order to please his family - and to quash any rumours about his sexuality.

Whatever the reasons, the couple were married at the Church of Saint George in Moscow on 18 July 1877. Their wedding dinner was famously held their wedding dinner at the Hermitage Restaurant.

Was Tchaikovsky gay?

Biographers have generally agreed that Tchaikovsky was gay. There is not universal agreement on this, however, nor on how much his sexuality - and the need to keep it a secret in conservative 19th-century Russia - played into the composer's unhappiness and mental distress.

Why is Tchaikovsky's music so emotional?

Tchaikovsky has been a special victim of clichés. For years the authors of books and programme notes about his music laid down the law about him. The trick was to create a spurious solidarity between the author and the reader by depicting Tchaikovsky as a self-obsessed and deviant outsider. First misrepresent his character, then connect that to the supposed character of the music, and then declare that both are somehow second rate.

A typical essay from half a century ago, by Edward Lockspeiser, speaks of ‘that terror of the mind against which Tchaikovsky fought for the greater part of his life’. His music’s ‘pretty tunes and dainty effects are distorted by an ecstatic, self-lacerating personality… his forked sexuality condemning him to subterfuge… It is never pity he expresses, but self-pity and with it self-love and self-hatred… He is the musician of indulgence.’ How extraordinary that anyone could write such nonsense about another human being, let alone about a genius such as Tchaikovsky. For hardly a word Lockspeiser writes is true.

Of course it is easy for me to write like this more than 50 years after Lockspeiser, because now the fact that Tchaikovsky was homosexual can offend none but the lonely bigot. Added to which, the careful work of historians has since shown how mistaken our view of Tchaikovsky was. There was a time when we assumed Tchaikovsky killed himself, even that he was forced to do so. And, knowing he finished the Pathétique Symphony only months before he died, we heard this Sixth symphony as a suicide note. But what if this masterpiece had nothing to do with suicide, nor even anything to do with death? What if the falling tears in the finale were falling for another cause entirely?

What were Tchaikovsky's main influences?

In a 1997 book called Russian Talk, the American ethnographer Nancy Ries investigates the idea of the ‘lament’ in Russian culture. She makes connections between the ritualised laments of peasant culture (at funerals or at weddings, as in Stravinsky’s Les Noces), the endless laments of modern Russians, and somewhere between them the laments of the great 19th-century Romantics. In Tchaikovsky’s work there are laments in his operas, his ballets and his songs, in his symphonic poems and symphonies, and most of all in the first and last movements of the Pathétique.

Some of the lamenting gestures Tchaikovsky shadows and transfigures in the framing movements of his Pathétique have their roots in the Russian opera, while others are to be found in the early 19th-century world of the Russian sentimental drawing-room romance – the everyday music of the better-off in Russia from the Napoleonic Wars till modern times. The characteristic ‘intonations’ (as Russian musicians call them) of the old romances were honed and developed by Tchaikovsky all his life.

Moreover, Tchaikovsky’s art was also shaped by his passion for the theatre. He completed ten operas and embarked on several others, as well as three of the greatest ballets ever written. And in different ways, each of his six symphonies is also at its root a drama. The ‘second themes’ (as Tchaikovsky himself labels them in his sketches) of the first and last movements of the Pathétique, then, are but the end and culmination of more than 30 years of preoccupation with the Russian lament, expressed within a dramatic context.

Tchaikovsky's 'Pathétique' Symphony: a 'programme' symphony?

Famously Tchaikovsky began by calling his Sixth Symphony the ‘Programme Symphony’, with ‘a programme that will remain a mystery to everyone – let them guess’. It was his brother Modest who later suggested the title Pathétique. Much has been made of the fact that Tchaikovsky never revealed what the ‘programme’ was. (Presumably, the reason why he let it be known that there was meant to be a programme was because he wanted to make clear that it was the fact that his symphony sounded like a drama that should matter to the listener, not what the drama was about.)

Nevertheless, there are clues within the Pathétique that at least suggest its programme was not death and suicide. First and foremost are those melody-laments in the first and last movements. The genre to which they belong was the sorrowing romance of the heart-aching lover, reflected in the shapes and inflections of the tunes. But most revealing are the rhythmic phrases, the reminiscent leanings on the beat and sobbing skips which, to anyone who has listened to hours of Russian song, suggest those same old tags: ‘Lyublyu tebyá, lyublyu tebyá! Mne bol’no, mnye grustno, mne zhalko!’ (‘I love you, I love you! I’m in pain, I’m sad, I’m unhappy!’)

Who did Tchaikovsky dedicate the Pathétique to?

Tchaikovsky dedicated the Sixth Symphony 'Pathétique' to his nephew Vladimir Davydov, nicknamed ‘Bob’. Bob was the son of his sister Sasha and the great love of his later years (but probably not his sexual partner). He wrote to Bob while working on the Pathétique: ‘The programme is imbued with subjectivity and composing it in my mind, I wept terribly.’ After finishing the first movement sketch in six (!) days, he wrote at the end ‘Glory be to Thee, O God! Begun Thursday 4th Feb. Finished Tuesday 9th Feb ’93.’ Two days later he wrote to Bob: ‘You cannot imagine what bliss I feel, assured that my time has not yet passed and I can still work.’

The manuscript of that six-day sketch has other scribblings, including the first draft of that extraordinary moment towards the end of the movement. Here, instead of the dramatic silence that had interrupted between the first and second subjects at their first appearance, the trombones rise out of the depths with cry after cry of that phrase so recognisable from all those sweet long-ago romances and operatic scenes that were only there to make us cry – a rising minor sixth that then falls back a semitone, in that distinctive skipping rhythm: ‘Lyublyu tebyá! Lyublyu tebyá! Lyublyu tebyá!’ (‘I love you! I love you! I love you!’).

When did Tchaikovsky die?

On 28 October 1893, Tchaikovsky conducted the first performance of the Pathétique in Saint Petersburg. Nine days later, Tchaikovsky died in the city, aged 53. He was buried in Tikhvin Cemetery near the graves of other major Russian composers including Alexander Borodin, Mikhail Glinka, and Modest Mussorgsky.

How did Tchaikovsky die?

The cause of Tchaikovsky's death is not known for certain. For a long time it was thought that the composer had died from cholera, after drinking unboiled water at a St Petersburg restaurant. More recently, however, some academics have speculated that the great composer may have committed suicide. It's unlikely that we will ever know for sure.

Why is Tchaikovsky important?

Tchaikovsky thoroughly deserves his place as both one of the greatest Russian composers - and one of the greatest Romantic composers. His music often wears its emotions on its sleeve: but Tchaikovsky was also a brilliant composer of tuneful and often very moving melodies, and colourful orchestration. Emotion is writ large in his music - and it's hard not to be moved by it. He also drew on Russian folk rhythms and the increasingly popular ballet form to write music with wonderful dancing rhythms. All in all, Tchaikovsky's music is perhaps among the easiest to fall in love with across the classical music canon. And that inaccessibility takes nothing away from the music's beauty, open-hearted emotion, rhythmic energy and more.

Gerard McBurney and Steve Wright

Other composer guides on www.classical-music.com

- Bach, Johann Sebastian

- Debussy, Claude

- Vivaldi, Antonio

- Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus

- Vaughan Williams, Ralph

Find all of our composer guides at https://www.classical-music.com/composers/

Authors

Steve has been an avid listener of classical music since childhood, and now contributes a variety of features to BBC Music’s magazine and website. He started writing about music as Arts Editor of an Oxford University student newspaper and has continued ever since, serving as Arts Editor on various magazines.