Kodály method: what it is, how it works and how it helps children learn music

As arts education strains under the pressure of cuts, the Kodály method for teaching music has never seemed more important, suggests Helen Wallace

Who was Zoltán Kodály?

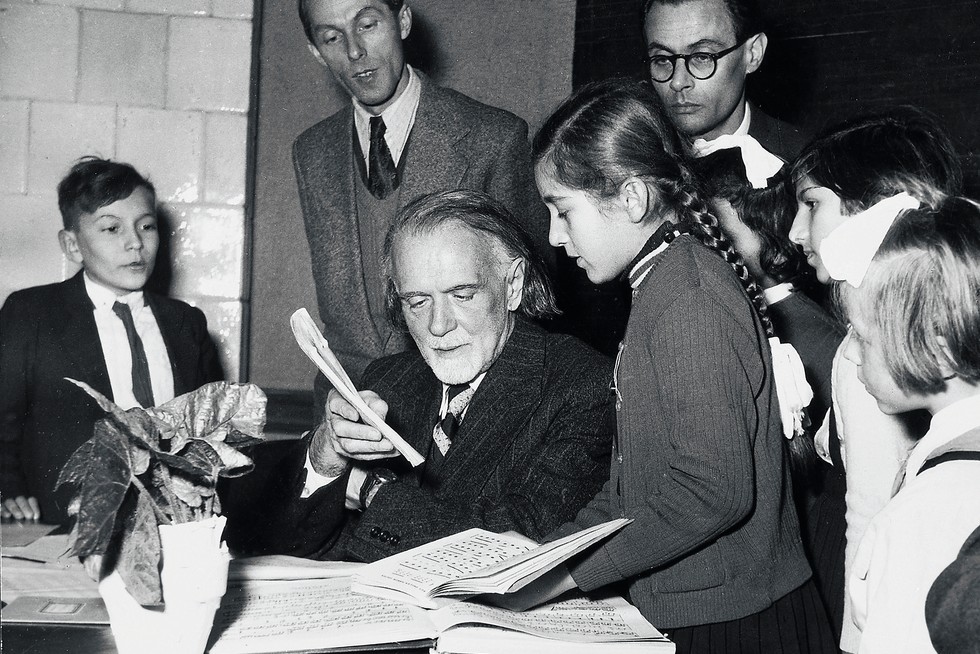

Composer Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) was also an ethnomusicologist, pedagogue and cultural visionary. The ethnic field recordings he made as a young man fed his own composing and the resurrection of a distinctive Hungarian repertoire. Far from being narrowly nationalistic, however, he was a cosmopolitan pragmatist.

When something worked, he embraced it. He was impressed by John Curwen’s system of hand signs for relative tonic sol-fa, used by non-music-reading massed choirs in 19th and early 20th century Britain. In Paris, he admired both the rigorous teaching of solfège (developed in the 19th century by Emile-Joseph Chêvé, Pierre Galin and Aimé Paris) and its equivalent rhythmic language.

Inspired by his belief that musical literacy was the birthright of every child, he returned to Hungary after the Second World War and surrounded himself with experienced teachers (including the gifted early years specialist, Katalin Forrai) with whom he began organising material pedagogically.

What is the Kodály method?

It was very much a joint enterprise, and while Kodály lectured and published exercises and songs, he was careful never to ‘fix’ a method. His principles, though, were clear: he wished to offer a unified, singing-based curriculum to every child, using high-quality music (be it folksong or art music) learnt initially through sol-fa and a gradual unpacking of the musical elements in logical steps. At its heart was the voice, the child’s own instrument: anything learned through the body is learned profoundly.

Nikhil Dally, founder of Kodály-based Stepping Notes classes in Surrey, amplifies the theme: ‘I came to Kodály having spent years teaching Javanese gamelan through singing. It’s a measure of the slight dysfunction of western society that we have become so obsessed with teaching instruments from notation. Around 90 per cent of other cultures learn music through singing: it’s fundamental.’

For pre-school children, simple, active game songs are learnt by imitation, with a focus on careful listening and individual singing. They begin with the minor third ‘soh-mi’, and gradually build up more pitches. Sol-fa is learned with hand signs which provide a physical link with the sound, and can be easily ‘read’ when learning new material. Sol-fa not only expresses relative pitch but the tonal function of each note in a scale or chord, dispensing with the need to focus on different musical keys. Children move from pentatonic to diatonic to modal scales, and experience pulse and rhythm through the body, gradually learning to read stick notation and, much later, on to stave notation.

Every child’s song or playground chant, however simple, is spring-loaded with musical information. Think of Pease Pudding Hot, a song with just four pitches, in 4/4 time: a song begging for physical action, a song for teaching the power of the rest, rhythmic patterns, the major third (try it in the minor), formal structure and simple harmony.

Children as young as three or four can engage with all this: later, elements can be consciously introduced. Far from being restrictive, such experiential knowledge allows them to play with the building blocks of music. I sing a phrase in sol-fa, a child responds by singing it backwards or adding a variant: it’s the beginning of improvisation. Instrument-learning may follow, but the aim is that children are still singing inside as they play.

More like this

Cyrilla Rowsell is a respected expert and teaches Kodály for the String Training Programme (4-11 year-olds) at the Guildhall School of Music. She knows from personal experience what children miss when they do no structured early years music.

‘Eleven years of piano lessons taught me something about playing the piano but almost nothing about music,’ she has said. ‘I was skating on the surface. If a child is shown a written crotchet they have no physical understanding what’s behind that. Kodály musicianship puts petrol in the tank in that it gives them a profound experience of music-making, through the voice, building up a repertoire of songs and giving them the unconscious knowledge of pitch-matching, walking the pulse, rhythm, phrasing and improvising – before making it conscious.’ Rowsell has also pointed out that a good Kodály teacher should be rigorously analytical, and should always be able to explain why they are working on any song.

Kodály once expressed the hope that ‘by the time we reach the year 2000 every child that has attended primary school will be able to read music’. While he achieved this in Hungary’s ‘music’ primary schools, sadly, in the UK today, where many primary schools have no specialist music teachers at all, this seems an almost outlandish ambition.

Yet his legacy thrives internationally. I’ve met practitioners using the Kodály with dementia sufferers, community choirs, autistic children, new-born babies, conservatoire graduates and in Colourstrings, the instrumental method developed from Kodály principles by Géza Szilvay.

Cyrilla Rowsell and David Vinden, director of the Kodály Centre of London, have created a seven-year curriculum of lesson plans and material for primary schools published by Jolly Phonics. In Scotland, Kodály-specialist Lucinda Geoghegan has written a progressive game-song collection under the imprint of the hugely successful National Youth Choir of Scotland – just two examples of many.

Kodály’s concept is all about how music works, and how it belongs to everyone. Fifty years after his death, when music is teetering on the edge of the EBacc, and children can make any music (with no understanding) at the touch of a screen, his vision has never been so relevant. We need to continue his fight, in his own wonderful phrase ‘for the elimination of musical apathy’.

Main image: Zoltan Kodaly talking to young students © Getty Images

Authors