Piazzolla, Astor

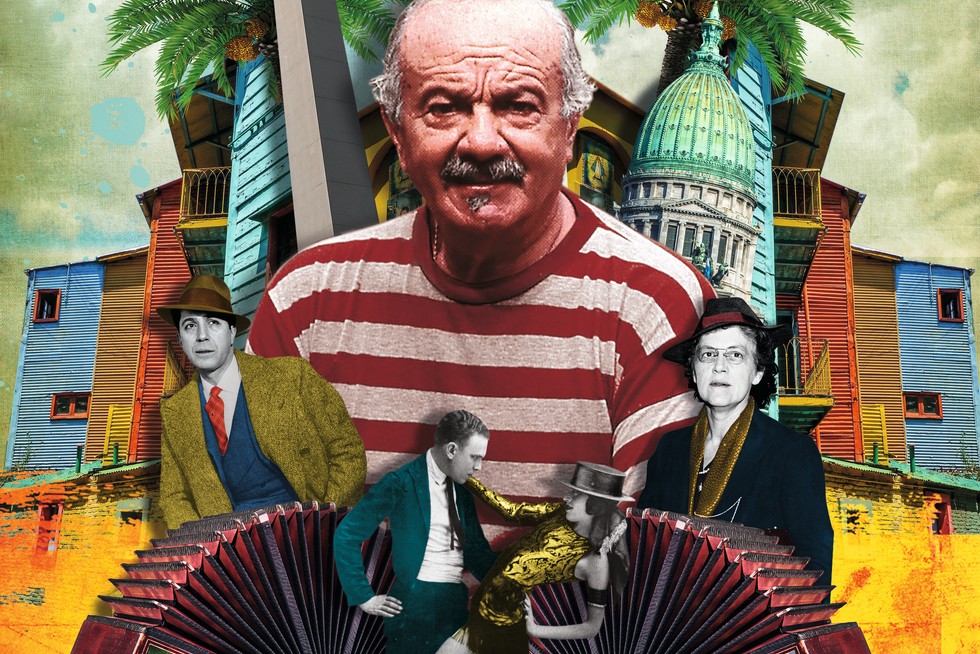

How one of Argentina's greatest composers Astor Piazzolla reinvented the tango, despite biting criticism back home. Rob Ainsley explores his life, influences and works

Some people might claim only Finns can understand Sibelius, or only the English can appreciate Vaughan Williams. Astor Piazzolla, who reshaped the tango during the 20th century, must have felt that only an Argentine could genuinely detest Piazzolla.

One of his many bands, his quintet redefined the national genre, elevating it from brothels and cabaret dives to the world’s concert halls. But Pablo Ziegler, the quintet’s pianist, lamented that while the classical world embraced Piazzolla’s music, it was often resented at home.

Piazzolla doesn’t understand tango, said writer Jorge Luis Borges; Borges doesn’t understand music, retorted Piazzolla. In concerts, audience jokers shouted ‘Bravo! Now, maestro, play us a tango…’. The quintet’s guitarist, Horacio Malvicino, even received death threats.

The problem was identity, and tradition. Argentina was built on immigration; Piazzolla’s own background was Italian. The tango – a late-1800s Buenos Aires hybrid of polkas, mazurkas, waltzes, habaneras, African candombé and native milonga – had become the national cultural icon, an intense powerplay-dance of the poor suburbs, with a self-contained music to match.

Carlos Gardel, the debonair boy from the backstreets, was its iconic singer and film star of the 1930s; through the 1940s, radio catalysed its first great Golden Age. Tango was Argentina. You messed with that at your peril. And Piazzolla’s music was for listening, not dancing to.

Who was Astor Piazzolla?

Astor Piazzolla was one of the greatest Latin American composers ever. He pioneered a new, jazz-infused, dissonant and rhythmically complex tango. He also composed several classical works which incorporate tango elements, among them a tango opera, María de Buenos Aires, a ballet and pieces for orchestra, of which his masterpieces are Four Seasons of Buenos Aires and the Concerto for Bandoneón and Orchestra.

When was Astor Piazzolla born?

Astor Pantaleón Piazzolla was born in 1921 in Mar del Plata, in Argentina; but he grew up in New York’s Greenwich Village, then a hand-to-mouth place of poverty and gangs, following the family's move in 1925.

When did he start playing the bandoneon?

Aged eight, he received a present from his tango-loving father: not roller skates as he’d hoped, but a bandoneon – the accordion-like ‘poor man’s organ’, tango’s definitive instrument. Nevertheless, he studied it, absorbing the music around him: traditional tango; klezmer; jazz; Gershwin; Mozart; Bach…

When did he return to Argentina?

In 1936 the family returned to Argentina. Piazzolla worked hard at his music – as a bandoneonist and arranger (with the great Aníbal Troilo’s tango band) until 4am, then rehearsing in the morning with the opera orchestra, or studying classical technique with Alberto Ginastera, Argentina’s premier composer.

Ridiculed for his halting Spanish, conscious of his gammy right leg, Piazzolla had coped by being combative and self-assertive. (He’d literally knocked on pianist Artur Rubinstein’s door brandishing a half-baked piano concerto, but Rubinstein was impressed enough to put him Ginastera’s way.) He constantly agitated to upgrade musical quality, pressing more sophisticated, complex arrangements into Troilo’s band than audiences – and players – were used to.

They didn’t like it. Pranksters sarcastically filled his bandoneon case with rubbish; he responded with itching powder or fireworks. Troilo was furious when Piazzolla abruptly left the band to go it alone in 1944, though not for long: he admired the young man’s ability and feistiness, nicknaming him gato (‘tomcat’). When Troilo’s widow gave Piazzolla the bandleader’s old bandoneon, it became a treasured possession.

Piazzolla yearned to be a classical composer, like his heroes Bartók or Stravinsky. His nationalism-flavoured Buenos Aires Symphony won a scholarship to Paris, to study with the legendary Nadia Boulanger. Lessons with the genteel, meticulous lady were ‘like studying with my mother’, he said. Her initial verdict, though, made him despair: his music was ‘well-written but lacks feeling’.

But one moment changed his life. Boulanger asked him about his music background, and Piazzolla reluctantly admitted to his tango work. She insisted he play her one; he responded with Triunfal. Boulanger, he said, took his hands and, in her ‘sweet English’, said: ‘This is the real Piazzolla. Don’t ever leave him.’

How did Astor Piazzolla change tango?

Liberated, and inspired by Gerry Mulligan’s jazz, Piazzolla returned to Buenos Aires determined to rejuvenate the tango which, against Elvis and the Beatles, was becoming the province of old folks and tourists. ‘Traditional bands used four bandoneons as a kind of wind section,’ explains British bandoneonist Julian Rowlands. ‘Piazzolla established it as a solo instrument, playing standing rather than seated, with the instrument on one raised knee. It restricts the technical possibilities, but highlights the soloist.’

Piazzolla added new sounds, sophisticated harmonies, dissonance and new instrumental line-ups. There was no singer, but a chamber-like feel to tango nuevo, with improvisation – ‘in a baroque rather than jazz sense though’, of embellishment and ornamentation rather than freewheeling melodic jaunts.

When did he invent Nuevo Tango?

On learning his father had died in 1959, he wrote Adios Nonino: tidal waves of piano emotion, then a typical Piazzolla mix of driving rhythmic tango and slow heart-tugging melody – perhaps his most-played work. In 1960 he formed his Quinteto Nuevo Tango, and the next 15 years proved his most musically fruitful as his works spread around the world.

Many Argentinians, however, thought Piazzolla’s tango nuevo detached, cold and cerebral. The reaction to ‘Balada para un loco’, a song from the operita (‘little opera’) project María de Buenos Aires, summed up the divisions. There were boos and derisive coin-throwing at its Buenos Aires premiere in 1969; four days later, 200,000 copies of the record had been sold.

Piazzolla continued to explore through the 1970s: film scores, jazz-rock, electric ensembles. His compositional output began to vary in quality, but his bandoneon playing remained compelling. At last he became financially secure, thanks to better royalties deals coming from France rather than Argentina.

Who was Piazzolla married to?

But his private life was in turmoil. In 1966 he left his wife Dede and their two children, shocking friends and family, and had a tempestuous seven-year affair with singer Amelita Baltar, whom he met while working on María.

At 55, he found emotional security, though: with Laura Escalada, a TV anchor who impressed him with her knowledge of Bach and Beethoven. (His press and TV relations hadn’t always hitherto been so amicable.) They moved to a splendid villa in Punta del Este, a Uruguayan resort just over the river from Buenos Aires, and enjoyed a life of music, cycling, barbecues and dinner parties – though Piazzolla’s enthusiasm for shark fishing showed he still enjoyed a scrap.

What was Piazzolla like as a person?

Like his music, Piazzolla’s character embraced both angelic and diabolic. He could be great company, a joker and raconteur in his fluent English and Spanish, even Italian and French. US vibraphone legend Gary Burton had nothing but warm memories of the demanding but positive musician he knew.

But one colleague said ‘on stage, he is a god; off it, he’s a bastard’. Piazzolla admitted being a terrible father to his children Daniel and Diana: music came first. He had many acquaintances but few friends. He blanked a biographer for eight years after a perceived slight to Dede. He recanted his earlier enthusiasm for Baltar’s voice after their breakup, saying ‘Love is blind. In my case it was also deaf.’

When did Piazzolla die?

His workload, and chain smoking, also had consequences: a heart attack in 1973; a quadruple bypass in 1988; a brain haemorrhage in 1990. He took two painful years to die, dyeing on 5 July 1992, in Buenos Aires when he was aged 71. He is buried in the city’s Jardín den Paz cemetery.

Piazzolla's legacy

Piazzolla could craft classical-form pieces (Tangazo, for instance, or the Bandoneon Concerto) but was no ‘great composer’ – Alberto Ginastera might smile wryly at the fact that his pupil’s BBC Proms performances (16 pieces in nine events since 2000) outnumber his own.

But Piazzolla was undoubtedly a great musician. He succeeded brilliantly in his aim to reboot the tango, creating a distinctive voice and vibrant sub-genre that went global, appealing to jazz, classical and popular listeners and musicians. The countless arrangements, recordings and performances of his pieces – whose royalties continue to earn Laura and his two children nearly half a million dollars a year – attest to that. No video footage of Buenos Aires is now complete without some Piazzolla. The little scrapper from Argentina won out in the end.

Main illustration © Matt Herring

Authors

Based in York, Rob is a man who uses his bike for everything – commuting, holidays, trips to Ikea… He's also been a professional cyclist – working for Deliveroo, is the author of The Bluffer's Guide to Cycling and 50 Quirky Bike Rides and his column on everyday cycling appears in Cycling Plus magazine every month.